CNM Ensemble Concert I

Sunday, October 6, 2024 at 7:30p in the Concert Hall

featuring guest percussionist and UI alumni

Steven Schick

with electronic support by Jean-François Charles

Program

The Ice is Talking (2018) | Vivian FUNG (b. 1975) |

| Steven Schick, percussion solo |

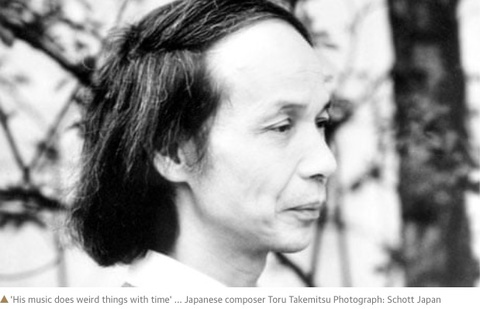

Rain Coming (1982) | Tōru TAKEMITSU (1930-1996) |

Déserts (1950-54) I. 1st episode | Edgard VARÈSE (1883-1965) |

intermission

Soundlines: A Dreaming Track (2019) | George LEWIS (b. 1952) |

Performer biography

Percussionist, conductor, and author Steven Schick was born in Iowa and raised in a farming family. Hailed by Alex Ross in the New Yorker as, “one of our supreme living virtuosos, not just of percussion but of any instrument,” he has championed contemporary percussion music for more than fifty years. In 2014 Schick was inducted into the Percussive Arts Society Hall of Fame. |

Center for New Music Ensemble

| Takemitsu - Rain Coming Joshua Stine, flute Aliya Zaripova, oboe Sayyod Mirzomurodov, clarinet Erik J Lopez Reyes, bassoon Erica Ohmann, horn Anna Kelly, trumpet Kolbe Schnoebelen, trombone Neil Krzeski, piano/celesta Miles Bolhman, percussion Yestyn Griffith and Michael Klyce, violins Rebecca Vieker, viola Hanna Rumora, violoncello Xiaowen Tang, double bass David Gompper, conductor |

| Varese - Déserts Joshua Stine, flute/piccolo Emily Ho, flute Sayyod Mirzomurodov, clarinet Lea Banks, Bass clarinet Erica Ohmann, Kristen Ronning horns Ryan Banks, Anna Kelly, Sara Lyons, trumpets Brady Gell, Kolbe Schnoebelen, Xiaoyu Liu, trombones Matt Sleep, John Reyna, tuba Neil Krzeski, piano/celesta Shaun Everson, Evan Tanner, Miles Bolhman, Zoe Dorr, McKenna Blenk, percussion Jean-François Charles, electronics David Gompper, conductor |

| Lewis - Soundlines Steven Schick, Speaker/percussion Sayyod Mirzomurodov, clarinets Christopher Anderson, alto saxophone Erik J Lopez Reyes bassoon Erica Ohmann, horn Yestyn Griffith, violin Hanna Rumora, violoncello McKenna Blenk, ensemble percussion Jean-François Charles, electronics David Gompper, conductor |

Program Notes

I grew up in Edmonton, and every year my family would vacation in the Canadian Rockies. I would greatly look forward to seeing the mountains, the majesty of the giant silhouettes, the clean, crisp air, and the proximity to nature and wildlife. I was invited back to the Banff Centre last year and decided to visit the Columbia Icefields as a bit of nostalgia for my childhood. That trip pained me deeply when I saw how much the glaciers had receded since the last time I was there, about 20 years ago. “The Ice Is Talking” is a work that is an emotional reaction to that experience. Vivian Fung’s The Ice is Talking, an evocative work for amplified ice and electronics, poses special challenges. Imagine the laughable sight of a percussionist hurrying three frozen blocks of ice through a southern California heatwave, hoping to reach his studio before they melt. Or imagine any group of instrumentalists, say a String Quartet rehearsing Beethoven’s Opus 131, needing to work quickly as their instruments literally disappear while they play. It seems comical. And then you realize that the sound of the ice becomes more beautiful as it melts: the scraping is more sharply etched and the harmonic tones at the edges of the blocks purer. Vivian’s aria for ice gathers force in its final moments as heated water is poured on the blocks. The cracking and dripping of melting are miniature and poignant echoes of the loud booming and zinging of warming spring ice on the midwestern lakes of my childhood. Alas, the ice begins truly to sing only as it is dying. (Steve Schick) JUNO Award-winning composer Vivian Fung has a unique talent for combining idiosyncratic textures and styles into large-scale works, reflecting her multicultural background. NPR calls her “one of today’s most eclectic composers” and The Philadelphia Inquirer praises her “stunningly original compositional voice.” |

Rain Coming is one of a series of works by the composer inspired by the common theme of rain. Entitled Waterscape, the intention was to create a series of works, which like their subject, that pass through various metamorphoses, culminating in a sea of tonality. Rain Coming is a variation of colors on the simple figure played mainly on the alto flute that appears at the beginning of the piece. Toru Takemitsu (1931-1996) was a self-taught Japanese composer who combined elements of Eastern and Western music and philosophy to create a unique sound world. Some of his early influences were the sonorities of Debussy, and Messiaen's use of nature imagery and modal scales. There is a certain influence of Webern in Takemitsu's use of silence, and Cage in his compositional philosophy, but his overall style is uniquely his own. Takemitsu believed in music as a means of ordering or contextualizing everyday sound in order to make it meaningful or comprehensible. His philosophy of "sound as life" lay behind his incorporation of natural sounds, as well as his desire to juxtapose and reconcile opposing elements such as Orient and Occident, sound and silence, and tradition and innovation. From the beginning, Takemitsu wrote highly experimental music involving improvisation, graphic notation, unusual combinations of instruments and recorded sounds. The result is music of great beauty and originality. It is usually slowly paced and quiet, but also capable of great intensity. The variety, quantity and consistency of Takemitsu's output are remarkable considering that he never worked within any kind of conventional framework or genre. In addition to the several hundred independent works of music, he scored over ninety films and published twenty books. |

Déserts, one of the first works in the early 1950s to combine acoustic instruments with recorded sounds, is the composer’s last completed composition and represents a breakthrough in his compositional development. The musical material heard in the ensemble is made up of sound objects - static sororities with clear identities that is not subject to change over time. The tape part assembles “organized sounds”, originally recorded on magnetic tape on an Apex tape recorder in 1953 - sounds of factories and percussion instruments. The two sound worlds never meet and are never brought together. As you listen to this work, imagine not only the physical deserts of sand, the sea with vast distances underneath the surface, or of outer space, but also the deserts in the mind of humankind, where one is alone in a world of mystery and essential solitude. And yet, the hope for mankind to reach spiritual sunlight is evident in the final instrumental episode. This highly dramatic work, in touch with the deeper, repressed emotions of world society at the time it was conceived, caused protest and violent reactions in conservative concert programs (wedged between Tchaikovsky and Mozart). It is now recognized as an exceptional example of truly humanistic music. (David Gompper) Edgard Varèse, (1883-1965) an American composer of French birth. Varèse has frequently been honored as the adventurous explorer of techniques and conceptions far ahead of his time. This view of his work as 'experimental' and valuable chiefly for its prophetic character has perhaps been overemphasized, but enthusiasm for the new was undeniably an important part of Varèse's personality. He produced in the 1920s a series of compositions which were innovative and influential in their rhythmic complexity, use of percussion, free atonality and forms not principally dependent on harmonic progression or thematic working. Even before World War I he saw the necessity of new means to realize his conceptions of organized sound (the term he preferred to 'music'), and, seizing on the electronic developments after World War II, he composed two of the first major works with sounds on tape. (Paul Griffiths) |

Soundlines: A Dreaming Track is George Lewis’s musical interpretation of percussionist and composer Steven Schick’s journal documenting his 700-mile walk from the US-Mexico border to the San Francisco Bay Area in 2006. Schick performs as speaker and percussionist, joined by a chamber ensemble featuring eight musicians and electronics. One day, in 2006, quite unexpectedly, I began a 700 mile walk.

George Lewis is an American composer, musicologist, and trombonist. He is Edwin H. Case Professor of American Music and Area Chair in Composition at Columbia University, and currently serves as Artistic Director of the International Contemporary Ensemble. Lewis has been selected as a Fellow at the Columbia Institute for Ideas and Imagination and will be in residence at Reid Hall in Paris for Fall 2024. A 2020-21 Fellow of the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin, Lewis is also a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Letters, a Corresponding Fellow of the British Academy, and a member of the Akademie der Künste Berlin, Lewis’s other honors include the Doris Duke Artist Award (2019), a MacArthur Fellowship (2002), and a Guggenheim Fellowship (2015). |